HG Wells or Enrique Gaspar: Whose time machine was first?

- Published

The HG Wells tale of a Victorian gentleman who voyaged through time on a time machine of his own invention was the one that captured the public's imagination - but it was not the first of its kind.

It may surprise science fiction fans to learn that it was a little-known Spanish playwright who gave birth to the idea of time travel via a mechanical contraption.

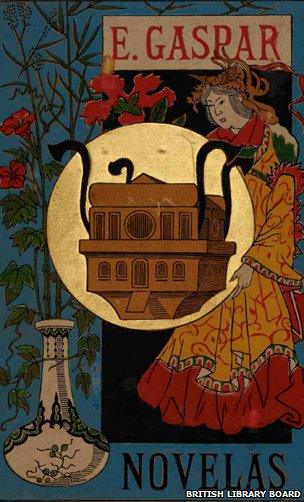

But Enrique Gaspar's hour may have finally come - his re-discovered novel will feature as one of the highlights of the British Library's first ever science fiction exhibition next month.

And, thanks largely to the persistence of Spanish science fiction fans, El Anacronopete will be translated into English for the first time, as The Time Ship: A Chrononautical Journey, next year.

The novel was published in Spain in 1887, beating HG Wells' The Time Machine into print by more than seven years.

Time travel

"This does seem to be the first literary description of a time machine noted so far," says Andy Sawyer, librarian of the Science Fiction Foundation Library at the University of Liverpool, and one of the curators of the British Library exhibition.

"There are, of course, much earlier descriptions of travelling through time - usually in a dream, but occasionally by some kind of magic.

"Edward Page Mitchell's story The Clock That Went Backward (1881) is usually described as the first time-machine story, but I'm not sure that a clock quite counts."

It was coincidental that the two Europeans dreamt up such a fantastical invention at around the same time (there is no indication that Wells read Gaspar's novel) - but this was the 19th Century, the age of new technologies, such as the steam engine, telegraph and electricity.

While Wells' time machine was a minimalist affair, Gaspar's was elaborate, an enormous rectangular ship constructed of iron and run on electricity.

"The original illustrations are wonderful and those coupled with the descriptions remind me somewhat of Dr Who's Tardis," says Mr Sawyer.

Like the Tardis, the time ship appears to be bigger on the inside than the outside. Gaspar's invention comes complete with a futuristic laundry, kitchen and observation deck.

El Anacronopete was originally written as a comic operetta while Gaspar, a flamboyant diplomat, was posted to China (see box).

He was a prolific playwright, but also wrote a few novels that dealt with the social impact of science and technology.

"The novel wasn't meant to be a serious scientific exploration, except as a way of looking at the past or the future as a way of satirising the present," says Mr Sawyer, who himself only recently found out about El Anacronopete.

"It's interesting to look at a novel that... was written for motives other than just a fascination with technology."

Rescued

Christine Buchanan, Gaspar's great granddaughter, describes him as "witty, inventive, generous, lively and undoubtedly a man of great charisma and personal charm".

But his greatest invention made little impact at the time. While Wells' The Time Machine has never been out of print and has been enjoyed the world over, El Anacronopete fell into obscurity.

"It had to wait for more than 100 years for the whole text to be rescued, says Yolanda Molina-Gavilan, professor of Spanish at Eckerd College in Florida.

Ms Molina-Gavilan is translating the novel into English for the Wesleyan University Press, along with Professor Andrea Bell, an expert in science fiction from Latin America and Spain.

Ms Molina-Gavilan says that it is thanks to the detective work of a Spanish science fiction club that El Anacronopete saw the light of day again. In 1999 it was distributed by the club on floppy disk.

It was subsequently reprinted in Spain on two more occasions, but is currently out of print. The whole text can be found in digital form in Google.

"There is a big science fiction fan scene in Spain, but academic circles have been slow to appreciate the genre," says Ms Molina-Gavilan.

Nineteenth-century Spanish literature is not associated with fantasy or science fiction, but it is believed Gaspar, who was well-travelled, was influenced by French astronomer and author Camille Flammarion and his fellow countryman, science fiction writer Jules Verne - author of Journey to the Centre of the Earth and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

And Verne's Around the World in 80 Days - which introduced readers to exotic lands beyond their wildest imagination - had been staged more than 400 times in France by the time El Anacronopete was published.

"Verne had been translated into Spanish and was a best-seller at the time," says Ms Molina-Gavilan. "I think Gaspar was trying to write a popular story, he was trying to catch on to something and maybe make a quick buck."

Humour

El Anacronopete is steeped in humour and in it Gaspar lampoons some of the ridiculous uses of science. He questions whether scientific progress and technological advances are the answers to everything.

But Ms Molina-Gavilan says the novel is primarily a fantasy adventure story.

"It is very, very different from HG Wells' novel, which is more sombre and serious. It is a romp, which features French prostitutes and Spanish soldiers - all aboard the time ship," says Ms Molina-Gavilan.

Wells uses the story of a time traveller to explore many of the social themes that obsessed him, such as evolution, class inequality and the relationship between science and society.

And while Gaspar is interested in exploring some social issues, he is never heavy, always "light-handed" says Ms Molina-Gavilan.

A central theme of the book is the quest by one of the protagonists, Don Sindulfo Garcia, to marry his niece Clara, with whom he has fallen in love.

He builds a time machine ostensibly to transport the pair back to a time when more chauvinistic customs would have allowed the union, says Ms Molina-Gavilan.

"His main motive is to go back to a time when women had to do what men wanted them to do," she says. Gaspar makes fun of Don Sindulfo - a rich gentleman scientist.

"Gaspar was basically socially progressive. He didn't like women to be subservient to men."

On their voyages, the characters witness a 19th Century Spanish battle, travel to ancient Rome, alight in 3rd Century China and end up at the moment of Creation itself.

Today, the notion of voyaging across the centuries is no longer consigned purely to the realm of science fiction. Scientists widely debate the possibility of time travel.

In the meantime, time machines continue to feature strongly in popular culture - from Dr Who's Tardis to Hermione Granger's Time-Turner, via the DeLorean car of the Back to the Future trilogy.

"There will always be a human fascination with travelling in time," says Andy Sawyer. "We all desperately find ourselves in situations where we wish we could have made different decisions."

Images and excerpted text from The Time Ship: A Chrononautical Journey (copyright 2012) by Enrique Gaspar, translated by Yolanda Molina-Gavilan and Andrea L Bell and reprinted by permission of Wesleyan University Press.

The science fiction exhibition, Out of this World, launches at the British Library in May.