Police march in review, 1883 Police march in review, 1883 |

|

|

Prepared by

|

Contributors

|

| Retired Inspector Sherman Ackerson |

Retired Deputy Chief Kevin Mullen |

| Dewayne Tully |

Sgt Robert Fitzer |

| |

Sgt Pete Thoshinksky |

The First Chief

|

In his inaugural address in August 1849, John Geary, the first elected alcalde (mayor/judge) in Gold Rush San Francisco, reminded the newly elected council that the town was "without a single policeman& . [or] the means of confining a prisoner for an hour."

On August 13 the council selected Malachi Fallon as San Francisco's first Captain (Chief) of Police. Fallon in turn appointed a deputy captain, three sergeants and 30 officers to comprise the first regular municipal police department in American San Francisco.

|

|

|

The city's first Chief of Police was born in County Athlone, Ireland in 1814 and moved as a young boy to New York City with his family. As a young man, Fallon ran a saloon frequented by politicians and served for a time as keeper at the Tombs Prison. When the gold mania seized the Atlantic States in late 1848, Fallon headed for California where he opened a store in Jamestown. In July , 1849 he returned to San Francisco on business where, he later wrote, "There were on Trial some persons for Rioting. The merchants of the town having heard of my former connections with Police matters, called to see me and offered inducements to remain and organize a police. The council met and appointed me Chief of Police at a salary of six thousand dollars a year, to have the whole control of appointments and Asst.., three sergeants and 30 men."

The motley little group of officers in 1849 had no training, no uniforms or equipment of any kind, or even an office from which to conduct police operations. To accommodate the housing problem, Chief Fallon housed his men at first in the pre-gold rush school house on Portsmouth Square.

The Public Institute

|

In 1847, prior to the gold discovery, San Franciscans had erected a one-room school house on Portsmouth Square (at Clay Street) to educate the town's few children. When news of the gold strike on the American River hit town, the pupils took off for the gold fields, their teacher not far behind. As the town exploded into city hood with the arrival of the 49ers, the little school house was pressed into service as a multi-purpose public building. In mid-1849 it served as a justice court and Police office. In October, the council acquired the brigantine, Euphemia, which was outfitted as a jail and moored out from Central Wharf (Commercial Street) at Battery. |

|

the old School-house on Portsmouth square

|

|

Prison Brig Euphemia

| Acquired by the council for $3500 from one of its own members in those pre-conflict-of-interest days, the "brig," as it was called, was served as the main post sentencing jail in San Francisco until May 1851, when it was sold to settle a judgment against the city. The frequent escapees from the insecure facility contributed to the public outrage leading to the formation of the first committee of Vigilance. Given the tendency of seafaring types to find their way into local jails while recreating ashore, the Euphemia may well have given a word (the brig) to that portion of a sip now used to describe the place where prisoners are held. |

|

| |

Prison brig Euphemia

|

The Graham House City Hall

| In may 1850, the council acquired the Graham House Hotel at Pacific and Montgomery streets for $50,000 - again from one of its members - and turned it into city hall. Executive and judicial officers were placed on the upper floors. A police Office and Jail "suitable for years to come" were placed on the bottom floor. The jail can be seen in the center foreground in the illustration at right. |

|

| |

Grahman House, City Hall

|

The scene depicts the excited attempt in February 1851 to seize and hang two wrongly accused Australian criminals. In 1850, San Francisco obtained its first charter which among its other provisions, provided for an elected marshal with "superintending control" of the police department. In keeping with common practice of the time, the marshal was to be selected by popular vote at yearly elections. Two months after the charter was adopted, the city council reorganized the little department, dividing the city into three districts and boosting the strength of the force to 75 officers and men.

Police Districts 1850

The first district, with its station house at First and Mission Streets in Happy Valley, extended from California street to Rincon Point. The Second District, with its station housed at City Hall at Pacific and Kearny, embraced the main business district. And the Third District, with a station on Ohio Street (now Osgood Place) covered the area from Pacific Avenue north to North beach. There was also a little lock-up or "calaboose" located in the First District station house.

As things were then, following each election the entire police department would be turned out and replaced by officers answerable to newly elected officials. It was not prescription for organizational success and on two - in 1851 and again in 1856 - the famed Vigilance Committee wrested control of the justice system from the regularly established authorities and administered justice on their own account. For all of that, the little department struggled for an organizational identity in the maelstrom of civic disorder, and implemented several needed innovations. The first rule book instructing officers in their duties was issued in 1853 and shortly thereafter a detective component was added to follow up on crime and prepare cases for prosecution. The Graham House City Hall burned in the June 1851 fire, the last major conflagration of the early days. In 1852 the council purchased the Jenny Lind Theater at Kearny and Washington and outfitted it as a city hall.

Jenny Lind City Hall

The Marshall's Office was located on the first floor facing Kearny Street, and the police office and jail were on the basement floor, with entrances on Dunbar Alley. (The adjacent El Dorado saloon was later absorbed into the government complex and the upper floor was badly damaged by an earthquake in 1865.) There was much opposition to its acquisition, including public demonstrations and a duel between a newspaper editor and a council member. The facility served fairly well until it was destroyed in 1895 to make way for a new Hall of Justice.

In 1856, San Franciscans voted in another charter that would govern the city for the remainder of the century. Under the provisions of that charter, the Department was to be governed by a commission comprised of the Mayor, the Police Court Judge and the Chief Executive Officer of the Department, now re-designated from City Marshal to Chief of Police. The position of Chief, like that of Mayor and Police Court Judge, were to be elective, but at two-year intervals. Officers were to be removed only for cause.

Up to that time there had been several attempts to place officers in uniform, resisted by the officers on the grounds that uniforms were a sign of European servitude as represented by servants' livery. In 1856 the new commission made wearing a uniform a condition of employment. A blue uniform, similar to that coming into fashion in eastern departments was selected. In 1862, however, the blue uniform was replaced by one made from gray cloth.

Uniforms

| Legend has it that San Franciscans chose a gray uniform in 1862 at the urging of a police commissioner with roots in the South. Given the pro-union sentiments prevalent in San Francisco during the Civil War, such an explanation is unbelievable. The real reason is that San Francisco was largely unpaved in 1860s and the dark uniforms would show the dust. |

|

It was also during this period, in 1864, that a series of telegraph stations were inaugurated to which officers would report on duty by telegraph before proceeding to their beats in what were then the outlying settled portions of the city. The first rudimentary telegraph system in 1864 tied the Station at Mission Dolores, the Harbor Station at Pacific and Davis, and the Chief's house at 930 Clay Street with the Central Telegraph in City Hall. As population pressure moved outwards, little stations were added at Hayes and Laguna and at Jones and Pacific in 1865. The following year the Fourth Street Station (at Fourth and Harrison) was in operation. |

| The Telegraph system, designed in part to mobilize officers quickly in case of disorder, was first put to the test in April, 1865 on the occasion of the riots which followed the arrival of the news of President Lincoln's assassination in the strongly Unionist city. |

Tools of the Trade

| From the beginning of American policing there was some question about whether officers should be armed. In the violent early days, the officers decided the issue themselves by carrying firearms. It was not until 1859 that Chief Martin Burke issued |

| the order that all officers should equip themselves "with a large revolver." As a backup in the days before the introduction of reliable firearms, officers also equipped themselves with large Bowie knives, which they carried in a scabbard under the breast of their uniform jackets. The illustration shows the badge and knife carried by Chief Martin Burke. |

|

| The 1870s, like the 1850s, was one of the more disorderly periods in the city's history. By that time, swelled by a population influx during the Civil War and economic hard times occasioned by the completion of the transcontinental railroad, which brought in cheap goods to the disadvantage of home industries, San Francisco descended gradually into an economic slump. Out of these conditions grew a class of hoodlums whose favorite pastime was fighting the police. Their other favorite target was the thousands of Chinese laborers who had been discharge in 1869 on the completion of the railroad. The 100-officer department had its hands more than full. |

Hoodlums and the Police

|

|

|

Newspaper cartoon of hoodlums contemptuously rifling police substations in the 1870s

|

|

The little unstaffed station houses, in addition to a telegraph connection to headquarters, had a temporary lockup to hold prisoners and space to store extra equipment. They were much like the Kobans of a later era.

Department staffing was gradually increased during the early 1870s in an attempt to match the growing population and increasing problems. Mounted patrols were established in the area west of Van Ness Avenue. In the First District, which then encompassed 20 square miles running from South of Market to Ocean Beach, the officers were equipped with a horse and a wagon for patrol purposes. There was also another wagon to transport prisoners from the outlying stations to the Hall of Justice.

|

| Much of the disorder during the 1870s was rooted in anti-Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the Great Riot of July 1877, in which it was shown that the Department was sadly understaffed to deal with the emergency. In an echo of the 1850s, a public safety committee was established, comprised of citizens equipped with sawed off pick handles (thus the Pickhandle Brigade) to put down the rioters. In the aftermath, it became obvious that the department was numerically inadequate to meet the challenges of the time. Over the next several years the department staff was increased from 150 to 400 members. |

|

The department also came of age organizationally. The city was organized into geographic districts and more substantial stations were established in the outlying districts. In 1878, fearing that radical workingmen would gain control of the city government and the police department, the state legislature moved control of the department to a stated appointed commission.

Part of the reorganization saw the reversion to blue "New York" type uniform, pictured here. The change suggests that the dusty streets of the earlier period were now paved and the atmosphere cleaner.

|

|

Police Districts 1880s

|

Because of the previous inability of officers to control vice in Chinatown, the Chinatown Squad, shown at left, was established in the early 1880s.

In 1889 the department established a patrol wagon/call box system through which officers could call their stations for the first time and obtain speedy backup assistance. Reserve officers standing by in stations would mount the wagons and respond quickly to calls for assistance and other emergencies. |

| In the mid-1890s the early wagons had open beds. They were later converted to the covered "New York" type, pictured below. |

|

|

Reorganization

| In the mid 1890s, as part of the Progressive political movement then sweeping the nation, the Department was reorganized. The rank of lieutenant was created to improve supervision and much of the old management staff was replaced. In 1898, San Francisco adopted a home rule charter which adopted civil service provisions, and when it went into effect in 1900, returned control of the police department to city authorities. |

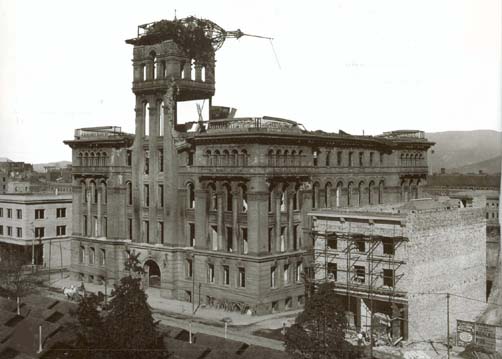

1906 Earthquake and Fire

| The San Francisco Police Department got off to a ceremonial start in the twentieth century with a new Hall of Justice built on Kearny Street in front of Portsmouth Square. Opened in 1900, the elaborate brick and terra cotta building was short-lived. Six years later, on April 18, 1906, the structure became, as a contemporary expressed it, one of the city's "damnest finest ruins," courtesy of the San Francisco earthquake and fire. |

|

| |

Police supervise clean-up crew after quake and fire

|

|

The earthquake and fire tested the department as never before. Police Chief Jeremiah Dinan, who had become Chief on April 5, 1905, had been to a performance of Carmen starring the legendary Enrico Caruso the night before. A few hours later, with terrified Caruso fleeing the city, vowing never to return (a promise he kept), Chief Dinan was ordering all police records to be taken out of the burning Hall of Justice to Portsmouth Square, where cinders threatened every minute to burn the canvas pulled over the documents. (In typical San Francisco style, officers poured bottles of beer from the saloon across the street onto the canvas; it worked.)

The department got a lot of help from the military, as soldiers from the Presidio, Angel Island and Fort Baker joined up with sailors and marines from the Mare Island in a joint effort to preserve order. This was a precursor to joint operations that would characterize emergency operation procedures in future policing plans.

The post-earthquake years saw a veritable building boom for police facilities. Richmond, Park and Ingleside stations were built, all in 1910, each designed by a noted architect, and Potrero, Northern, and Harbor stations soon followed, in 1913. The new Hall of Justice, thoughtfully constructed this time with a steel frame and concrete floors and roof, opened in 1912 on the same site as the earlier Hall.

This was also a time of innovation as well as building. The department was one of the first in the country to use fingerprinting to identify criminals. In 1909, the department instituted what would later evolve into the Solo Motorcycle Unit when Chief Jesse Cook (appointed 1908) detailed three officers to motorcycle duty to stop speeders (then known as "scorchers") and other reckless motorists. Chief David White (appointed 1911) was the first to devise a modern record-keeping system. San Francisco was also one of the first police departments to hire women, when in 1913, three women protective officers joined the SFPD.

|

|

Ruins of the Hall of Justice on Portsmouth Square, 1906

|

The 20s and 30: Crime, Prohibition, and Labor Unrest

| At the end of World War I, in 1918, the SFPD had around 930 officers. The lawlessness that characterized the city during the Gold Rush began to take different turns, like the bloody Chinatown Tong Wars (they would be known as gang wars now) of the early 20s, and the flaunting of Prohibition laws during that decade. The tong wars were resolved with an early from of community policing, which would eventually become the department's ruling philosophy. Under Chief O'Brien, Inspector Jack Manion brought Chinatown leaders together, and persuaded the tong leaders to sign an agreement ending the violence. Because of Manion's work, the tong wars stopped, and the Chinese community came to respect and admire him. |

| The era of Prohibition, which extended for 13 long years, form 1920 to 1933, provided a unique example of law enforcement dealing with a basically unenforceable law. The law was brazenly violated by everyone from big-time distributors to a man called the "Walking Boot-legger," whose multiple inside pockets of his long coat concealed not only flasks of booze, but a glass as well, as he went along the waterfront selling his moonshine by the glass. The Property Clerk's Office was a vast liquor store. No sooner were the |

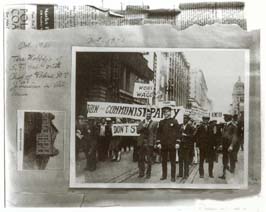

Chief W. Quinn leads Wobbly march on Market Street Chief W. Quinn leads Wobbly march on Market Street |

| bottles' contents poured down the drain after court proceedings had ended than more full bottles were hauled in as evidence. The Waterfront Strike of 1934, pictured below, prefigured the confrontations police would experience on V-day 11 years later and, much later, in the racially based riots and San Francisco State demonstrations |

| over Vietnam in the 60s. A distressful time, striking dock workers were pitted against police and federal troops, and the result was a mini-war, with a number of dock workers killed in the gunfire and tear gas melee. It was a case of police drawn into a workers' conflict that should have been mediated by the workers and bosses through arbitration |

The waterfront strike of 1934 The waterfront strike of 1934 |

|

from the beginning, but animosity and temper prevailed, with unfortunate consequences.

Between the end of prohibition and the beginning of World War II, the Department continued to grow in manpower as the city itself increased in population. The department's years were marked by advances in training (Chief Daniel O'Brien [appointed 1920] instituted the Police Academy in 1923, the first in the nation; in technology (officers began to use the police radio in 1932); by new facilities (Park Station, opened in 1932); in organizational restructuring to meet department needs better; and in a major change in uniform design, namely, a short, single breasted dress coat.

|

General strike 1934 General strike 1934 |

|

Post World War II: The 40s and 50s

| The end of World War II was something of the Gold Rush days all over again in that there was a surge of people, in this case war workers, from all over the world converging into the city. August 14, 1945 might have marked the end of the war, but for a while San Francisco was something of a war zone, when celebration of military personnel turned into full-scale riot that lasted three days. Chief Charles Dullea (appointed 1940) had to use all his resources |

Officers with government issued gas mask Officers with government issued gas mask |

|

to quell the actions of what he unequivocally called "the unbridled and unrestrained acts of a lot of undisciplined men in uniform."

If V-Day put the department's crowd control tactics to the test, the 50s presented a new kind of crime to deal with: organized crime. No longer an East Coast phenomenon, organized crime was making inroads into the West Coast, with a marked presence in San Francisco. Police Chief Francis Ahern (appointed 1956) and homicide Inspector

|

President Eisenhower greets security escort. Chief Tom Cahill is at right President Eisenhower greets security escort. Chief Tom Cahill is at right |

| Thomas J. Cahill (who, upon Chief Ahern's sudden death would be appointed Chief, in 1958), had gained national recognition in their handling of the mafia murder of Nick de John in 1947. (de John , along with a couple of his cohorts, had absconded out of Chicago with some mafia money. The mafia was not please with this. De John's body was eventually found in the trunk of a car parked at Laguna and Greenwich; He'd been strangled with fishing line.) Senator Estes Kefauver's committee on organized crime recognized Ahern and Cahill's investigation on this case, and the committee relied heavily on their expertise. |

The Turbulent 60s and 70s

| Out of the 60s came social unrest of varying kinds that would test the department to the utmost: the hippie movement, marches for social justice, race riots, university demonstrations over Vietnam. Chief Cahill, during his long administration (from 1958 |

San Francisco State strike 1969 San Francisco State strike 1969 |

to 1970), was singularly able to deal with a changing society. Hiss was a direct, no nonsense, approach combined with an understanding of where people were coming from, a compassion for their frustrations and predicaments.

Shortly after the bombing of Birmingham, Alabama church, in 1964, in which four girls were killed, 23,000 persons marched up Market Street for a planned demonstration |

|

at Civic Center, the first of its kind in San Francisco, and Cahill was on the podium to address the crowd. He knew they didn't care much for the police, so he made sure his officers maintained a low-key presence on the periphery of the crowd. His words to them were simple - "We'll all get along well here" - and his positive gesture, dropping some money into a container marked for the victims of the bombing, had a tremendous effect on everyone. When the crowd dispersed after the last speaker, there was absolute order.

Cahill led the Department through civil disorders, like the riot that took place after an officer shot and killed a teenage car theft suspect in Hunter's Point (he made sure that the 2,000 National Guardsmen Governor Pat Brown ordered into the city maintained the lowest possible profile); the demonstrations over Vietnam at San Francisco State ("Leave peacefully or get locked up"); and the 60s hippie movement, where enforcement of laws was combined with Cahill's compassion for parents of those kids who had left home to achieve flower power (in one case, he located the daughter of parents who had personally sought his help; through sheer intelligence work, he located the girl in Seattle).

In a terrible shift of events, the end of the 60s and the early 70s was a violent time for officers. In one year alone, 1970, four officers were killed in separate incidents, the victims of hatred and resentment taken to the level of assassination.

|

Haight Street sweep 1969 Haight Street sweep 1969 |

| If crime had once manifested itself as tong wars, bootlegging, and organized crime, the 70s saw a new type of crime involving the serial killer. The Zodiac, who claimed a number of victims (but only one in San Francisco) has never been found and the case is still officially open. The Zebra killers randomly shot to death 12 persons during 1973-74. A dragnet ordered by Mayor Joseph Alioto and intensive police work resulted in the arrest of four suspects, convicted with life sentences. The 70s was highly politicized era characterized by radical activity, as exemplified by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) whose most famous representative, Patty Hearst, was finally arrested in San Francisco for her involvement in an organization that used deadly force to publicize its convictions. The decade closed with one of the most shocking events in San Francisco History: Supervisor Dan White's double killing of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk on November 22, 1978. The manslaughter verdict and the relatively light sentence resulted in the siege of City Hall during the "White Night" riots. As police cars burned in the street, their sirens wailing from the shorting of melted wires, officers ringed City Hall to protect it. |

Police cars burn in "White Night" riot 1979 Police cars burn in "White Night" riot 1979 |

The Progressive 80s and 90s

| A large component of the department's later administrations involved talking with persons who had grievances, inviting them to work on solutions. Working with the community would become the hallmark of future administrations. |

|

|

The partnership is one of the special aspects of the department. And in its combination of recruiting men and women to reflect the city's extraordinary diversity - people of color, women, gays - and in its sharing of ideas, the San Francisco Police Department is unique. |

|

The current department is one that seeks out the latest crime-fighting technology. Its communication system is continuously updated. Its police facilities have been extensively remodeled or rebuilt. It's compliment of over - 2000 officers are among the best trained in the country. But it is community policing- ranging from |

| hosting events for youth and seniors to citizen patrols that work with officers, from community meetings to Citizen's Police Academy - that glues it all together. It is the ongoing working relationship between officers and the communities they serve that makes policing work. |

|

|