Thursday, June 14, 2007

Executive Council rebukes Presiding Bishop

The Episcopal Executive Council said that Anglican leaders, called primates, cannot make decisions for the American denomination, which is the Anglican body in the United States. "We question the authority of the primates to impose deadlines and demands upon any of the churches of the Anglican Communion," the council said in a statement, after a meeting in Parsippany, N.J.

Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori had endorsed the unanimous communique from the Primates Meeting in Dar es Salaam earlier this year, which stated that the Primates will establish a pastoral council, including a primatial vicar to care for those parishes and dioceses in conflict with the Episcopal Church. The statement from the Executive Council, following up on the recent House of Bishops meeting at Camp Allen, effectively ends all hope that the Episcopal Church will cooperate with the process of healing and reconciliation.

Schori has been vocal about the need for the reconciliation, for a "period of fasting" on same-sex blessings and ordinations, and for the willingness to cooperate with the Anglican Communion. The communique, which the Presiding Bishop supported, noted:

24. The response of The Episcopal Church to the requests made at Dromantine has not persuaded this meeting that we are yet in a position to recognise that The Episcopal Church has mended its broken relationships.

Despite what might be her best efforts, it appears the Episcopal Church is just not interested. Or perhaps better stated, is vigorously opposed to reconciliation with the Anglican Communion.

Saturday, June 09, 2007

Friday, June 08, 2007

If you can't eat red meat on Fridays...

Thursday, June 07, 2007

The Eucharist and the Future

Christian worship is the living expression of the spiritual piety and doctrinal belief of its adherents--both in the present and in the past. Since the religion of the disciples of Jesus is characterized by eschatological overtones, it is natural that there are deeply rooted eschatological characteristics to Christian worship as well. Looking toward the consummation of God’s kingdom is the dominant context for worshiping as a part of that kingdom. It is worship in spirit and in truth. As such, it is a prayerful anticipation of, and spiritual participation in, the beatific vision of God.

Eschatology concerns the study of last things in Catholic theology. It covers death, final judgment, heaven, hell, and so forth. However, in the liturgy, the dominant eschatological theme is the final realization of the kingdom of God. This theme is embedded in the origin and theology of Christian eucharistic worship. We can also see eschatological elements develop over time in the manner in which the worshiping community performs its liturgy. We shall look at possible reasons for development in the eschatological shape of eucharistic worship, considering the present state of affairs and possible future developments.

The Supper of the Lord: Covenant Sacrifice and Kingdom Feast

The Lord’s Supper was established by Jesus Christ as a memorial of his passion, the significance and meaning of which includes his incarnation, life, death, resurrection, ascension, and his parousia or eschaton (his “coming again in glory”). The word parousia means appearance, presence, or arrival. It is the natural fulfillment of the redemptive work of Christ, who the Scriptures call both the Alpha and the Omega—the “beginning and the end.”

Salvation history is a chronicle of the redemption, and as such is also the chronicle of a new covenant, which Jesus calls a “covenant in my blood,” that heralds the kingdom of God. Every covenant is established through the act of sacrifice, and Jesus offers sacrifice beginning in a meal with his disciples to inaugurates this covenant.

John’s gospel presents a vivid picture of the sacrificial inauguration of the covenant. The Passover is the sacrifice and memorial meal representing the old covenant. Jesus has come to establish God’s kingdom with a new covenant. His memorial meal ushers in the hour of his glorification. In a parallel action, Jesus is slain along with the sacrificial Passover lambs so that he is truly “the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world.” The lambs are slain to forgive sin, for according to the Law, “without the shedding of blood, there is no forgiveness of sin.” Yet the sacrifices of these animals are but a type of the sacrifice of the true Lamb of God. Jesus came not to abolish the law, but to fulfill the law.

In examining the inauguration of a new covenant through the sacrifice of Jesus, we must consider questions like, What was offered? by whom? to whom? when? and why? In the act of sacrifice, there are two main actions—the oblation and the immolation. The oblation is an offering by a priest of gifts to God as a sign of God’s supreme dominion and our dependence upon him. This is often accompanied by some thanksgiving or petition (e.g. for the remission of sins) with the hope that as the gift is pleasing to God, so he may be moved to grant the petition. The immolation is the conclusion or consummation of the act of sacrifice. The gift which has been given to God is now destroyed or in some way rendered incapable of performing it’s normal function. For example, an animal offered would be killed so that it is no longer a living animal, or a cup of wine would be poured out or grain burned so that it could no longer be consumed. In the sacrifice of the new covenant, Jesus is himself both the Priest and the Victim—the one who offers and that which is offered.

From Anticipation to Realization

The sacrificial meal is the realization of the sacrificial petition. In the case of the Christian community, this feast is the memorial of the redemptive work and person of Jesus Christ and it is therefore the realization or actualization of the Kingdom established by the new covenant sacrifice. At his Last Supper, Jesus prays for the realization of the Kingdom, as is also reflected in the Didache: “As this piece was scattered over the hills and then was brought together and made one, so let your Church be brought together from the ends of the earth into your Kingdom.”

Jesus commands his disciples to love one another and joins his priestly petition for their unity in the Spirit with the offering of himself. He takes signs of human life and labor to become his own life and labor. Jesus offers them in thanksgiving to the Father and gives them back to the disciples as tokens of the transformation realized through the new covenant sacrifice of his broken Body and shed Blood. At this point Jesus has offered himself—body, soul, and divinity—to the Father. After his oblation, Jesus is willingly taken into custody of those who would destroy him. The next day he is slain as a Paschal Lamb and this act of immolation concludes the sacrifice in which his Body is broken and his Blood poured out for the life of the world.

In the early Christian communities, the people gathered on the Lord’s Day to participate in the sacrificial meal that was performed after the example of the Last Supper in fulfillment of Jesus’ command, “Do this as my memorial.” The difference for them is that the oblation of the meal occurs after Christ has been immolated on the cross. In the spirituality of the Eucharist, therefore, the believer tends to work backwards. In the meal, he or she is to receive the resurrected life of Jesus. Therefore, in thanksgiving the believer retreats in time to the self-offering that Jesus made before his passion. The believer offers him or herself along with Christ, whose passion is commemorated in thanks and praise for the life granted on the far side of the cross. Although Jesus’ work on Calvary is an event at a moment in time, through this Eucharistic memorial, it takes on an eternal character.

Worship in the kingdom is a participation in the work of redemption through praise and thanksgiving. St. Paul urged his readers to “present your bodies a living and holy sacrifice, acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.” The believer offers him or herself with Christ, who in bread and wine took signs of human life and labor and incorporated them into the gift of himself. What was at the Last Supper a banquet of anticipation is now a communal feast of realization. In the post-resurrection community, the sacrifice and feast take on an almost cause-and-effect relationship: “Christ our Passover has been sacrificed. Let us therefore celebrate the feast.” It is by participating in the eucharistic banquet that we “proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” and thereby participate in the kingdom he established.

The Shape of the Sacrificial Banquet

Early in the history of Christian worship, the liturgy was increasingly taken to be an icon of heavenly worship. We see Eucharistic overtones in the picture of the marriage banquet of Christ and his Church at the end of history in the Revelation of St. John. Debate continues over which was the initial influence—whether practice shaped the description or whether the description was more influential in shaping practice. But the conclusion is unavoidable that the liturgy increasingly was characterized as the earthly image of heavenly worship.

The legalization of Christianity in the empire during the fourth century and it’s resultant adoption of official and public trappings—such as the features of court ceremonial—undoubtedly influenced Christian architecture and worship. But was this influence dominant, or were the developments of this period more internally driven as the religion was now free to express itself in the open and evolve unfettered? It is likely that the eschatological shape of the liturgy itself had a deeper and more abiding influence on the eschatological shape of sacred space in Christian art and worship.

By the ritual high-water mark in East and West during the Middle Ages, the heavenly beauty and sublime nature of Christian worship was taken to be one of its most important attributes. Before the conversion of Russia, Duke Vladimir—unsure of which faith to follow—sent emissaries to visit the various churches of Europe. Reporting on their experience at the Ecclesia Hagia Sophia, the mother church of the East in Constantinople, they said, “We did not know whether we were in heaven or on earth. It would be impossible to find on earth any splendor greater than this . . . Never shall we be able to forget such beauty.” Later on, Fredrick Faber—an English priest of the 19th Century—similarly became famous for his impression of the Latin Mass as “the most beautiful thing this side of heaven.”

The seasons of the Church year and the development of the rites of Easter and Holy Week are examples of increased eschatological features of Christian worship. Obviously, the season of Advent and the feasts of Ascension, Pentecost, All Saints, and Christ the King are relevant to this development. However, our main concern in this treatment is the standard weekly celebration. The most significant and earliest development is Sunday worship.

In the New Testament period, the Church gathered on “the Lord’s Day” which is the first day of the week. Worship was held on this day as it had been the day of the Lord’s resurrection from the dead and also the day of his subsequent appearances to the disciples. The Lord’s Day is also the “eighth day” of the week—the day on which the new creation begins. The Epistle of Barnabas, dated around the latter New Testament period, ascribes this significance to the institution of the Lord’s Day even before the importance of the resurrection, saying, “I will make a beginning of the eighth day, that is, a beginning of another world. For that reason, also, we keep the eighth day with joyfulness, the day also on which Jesus rose again from the dead.”

Therefore the Lord’s Day signifies both the day of Jesus’ resurrection and the dawning of the new heaven and new earth described by St. John in his Book of Revelation. The precedent of the eighth day as the day of the redemption and the new creation is shown in the development during the second century of celebrating Easter—the Christian Pasch—on a Sunday each year rather than on the particular day corresponding to the 14th of Nisan, when the Jews celebrated the Passover.

The eschatological shape of the Eucharistic rite guided the development of two more significant features—the setting of the holy Mysteries and the characteristics of the minister celebrating them. The celebrant of the holy mysteries was increasingly seen as sharing in the mediating priestly ministry of Christ. This is natural since the minister both stands in the place of Christ in celebrating the Eucharist, as Jesus did with his apostles, and he also prays to God from the assembly in the name of all present. This is why his priestly prayers in the liturgy are always first-person-plural.

Thus, the minister himself took on more of the priestly attributes we see in Christ. He, more than anyone else in the community, is the visible sign or icon of the kingdom. The most obvious form of this early development is the tradition of priestly sexual continence. Celibacy in the New Testament is a sign of the kingdom of heaven where God’s people “neither marry, nor are given in marriage.” In his ministry, Jesus spoke of this great mystery to those who are called, saying, “there are also those who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. He who is able to accept this, let him accept it.”

Many of the first disciples of Jesus (as far as can be known) were married. Some of the early Church Fathers relate to us the tradition that upon entering their ministry, the apostles set aside their wives for the sake of the kingdom. While they did not at all abandon their wives, the discipline was that they were to live as siblings in regards to sexual relations rather than as husband and wife. This practice, they say, continued in the appointing of elders and deacons in churches. Since they needed seasoned men with whom to entrust this ministry, they often had to pick from married men. This practice is reflected in the later New Testament letters. The first major breakdown of this ideal was that some clerics viewed the process as an annulment and a reversion to bachelorhood. As a result, they saw themselves as free to contract (another) marriage. The abuse is addressed with the admonishment that they are only permitted to be the “husband of one wife.”

In the Eastern Church, the discipline developed in a more relaxed form as a matter of practicality. It was most common for the typical parish priest to be married. The practice became standard that married men could be ordained, yet the charism of celibacy for the sake of the kingdom continued to be highly esteemed, and the episcopate became reserved to celibate candidates. While the East (with its emphasis on mystery and symbol) saw the minister as representing the kingdom, the West (with its legalistic perspective) saw the ideal of the kingdom as a discipline to be enforced.

In the West, the ideal of celibacy as refraining from contacting marriage and thus from exercising the rights of marriage was interpreted more strictly. The Synod of Elvira was the first to issue canons relating to what was considered to be the norm of clerical continence. However, strict enforcement of this discipline was not firmly established until the reforms of Pope Gregory VII (and even after, lapses of the rule were not unknown and such marriages were held not only unlawful but also invalid by the First Lateran Council in 1123).

But in both East and West, the Church viewed the minister at the altar as an icon of priestly purity. His continence was an image of participation in the realized life of the kingdom. He functionally continued the Levitical tradition of abstaining from the rights of marriage before times of priestly service. But ontologically, he was a symbol of the higher calling of total continence, exercised by Christ the high Priest—the unique source and irreplaceable model of his own priesthood. Similar to the monastic vocation, the parish priest was a living witness to the Kingdom realized in humanity.

The Procession to Paradise

The priest guides the eschatological shape of the celebration by its performance. He leads the procession toward the sanctuary of heaven. Salvation history is recounted in the hymns and readings, the work of Christ is proclaimed, the Gospel of the Kingdom is preached, the people make their prayers and offerings, and the priest takes them into the sanctuary to make the offering as the great high Priest, Jesus Christ has entered into the sanctuary of heaven to make the perfect oblation.

So contextualized, the orientation of the church building in which the liturgy is performed “expresses the hope and confidence of the Church in him whose coming was from the East in the historic past, and will be again at the glorious Parousia”—the Eucharist as efficacious memorial of the one, and anticipation of the other, joining the two in the present.

The liturgical action as a whole carried with it a kind of movement led by the priest. This motion was always toward God (e.g. “Let us attend to the Lord,” “Let us turn to the East,” “Lift up your hearts,” etc.). German liturgist Klaus Gamber noted: "When the faithful increasingly moved into the center nave, they resembled an army formation, and a certain dynamism was created, something like the procession of the people of God through the desert towards the Promised Land. Facing East was to indicate the direction in which the procession was to move: towards paradise, which had been lost and was to be found again in the East. The celebrant and his assistants were at the head of this procession."

The development of iconography and other Church art can rightly be seen as a continuation of the process of making the appearance of earthly worship more akin to the heavenly worship described in the Bible. The sanctuary is separated from the nave (and chancel) by some kind of barrier representing the veil of heaven and marking it off as sacred space. In the East, this developed into the iconostasis that contained, as it were, iconic "windows" into the heavenly sanctuary. In the West, the reredos came to fulfill the role of showing the heavenly character of the sanctuary. Prior to a cross or some image of the crucifixion, the earliest churches had an image of the risen Christ (often depicted as the ruler and lawgiver) in the apse above and behind the altar at the eastern end of the church. The priest stood before the altar and faced this image when offering sacrifice.

This practice enacted the apostolic tradition of watching for the Lord’s return. John of Damascus explains: "When ascending into heaven, he rose towards the East, and that is how the apostles adored him, and he will return just as they saw him ascend into heaven . . . Waiting for him, we adore him facing East. This is an unrecorded tradition passed down to us from the apostles."

Worship as the Icon of Heaven

With the delayed parousia, there is a shift in theological discourse from an immanent eschatology to a realized eschatology. Christ’s rule and the life of his Kingdom comes to be seen more as something to partake in now than something to simply be anticipated.

This trajectory is paralleled in Christian worship which increasingly saw the earthly liturgy as a model of, and then as a participation in, the worship of heaven. Though development occurs, it is not so much a change of doctrine as it is a change of perspective. The transition is evident even in the New Testament period and reaches a climax in the late Middle Ages when the Church viewed itself as coterminous with the Kingdom of God and the society called Christendom as having reached a perfect equilibrium. Joachim of Fiore even theorized that from 1260 this situation would bring about a perfect third age (the Age of the Spirit), where the ideal of the kingdom of heaven is realized on earth.

To assist at the Eucharistic liturgy of the Church is to participate—more clearly than at any other time or in any other way—in the life of the Kingdom. The growth in ritual and ceremonial toward the high Middle Ages (the adoption of the sanctus, incense and torches, processions, icons and other church art, the extended division of the sanctuary from the nave, the veiling of the canopy and altar, the silence of the canon, etc.) represent a move toward a liturgy of realized eschatology. It is a worship that brings the parousia to the hear-and-now.

Ironically, the shift toward our present state of affairs most likely occurs at the high-water mark of ornate ceremonial—the high Middle Ages. When ceremonial is at its height, liturgical worship begins to be more heavenly spectacle than a sharing in heavenly life. The worship of clergy and laity become parallel (rather than integrated) actions. To assist at Mass comes to mean witnessing the elevation rather than praying the liturgy. At this point, liturgical performance almost becomes entertainment—a thing to witness and enjoy. Liturgy is something that appeals to tastes: in music, in architecture, in art and craftsmanship. The focus of the liturgy began an extended shift from a vertical shape (concerned with things of above) toward a horizontal shape (concerned with the here-and-now). In the Baroque period, going to the High Mass was equivalent to going to the opera (an institution which had developed outside the Church, but deeply affected Church life and worship).

The Current State of Affairs

Our modern state of affairs is probably not related so much to a return to an immanent eschatology like the early Church as it is to simply the dawning of a post-realized eschatology. Our age has an eschatology without the eschaton. We are a people who for the most part no longer watch for the Lord’s coming, and now that hope hardly even crosses our minds. Our society is too concerned with the present to give much consideration to the past or the future. This is simply the by-product of the secularization of Western civilization. In cultures where Christianity is relatively new, we find features of the immanent eschatology in worship that characterized the early Church.

The shift in liturgy towards the Baroque period was from participation to pageantry. Even the revival of ritualism in the Romantic Period was probably not a renewal of the eschatological shape of Christian worship. As a reaction to secularization, it was a liturgy that focused on the kingdom, but it was deficient in moving too far from a biblical theological perspective. Rather than a worship that looked toward the glorious parousia in the future, it looked longingly back to the Medieval "Age of the Spirit," when the kingdom had existed on earth.

A need was felt in many Church circles to return to more simple worship in which the laity can be actively involved. The shift from partaking in heavenly life toward witnessing heavenly spectacle occurred because of an alienation of the laity from an active role in liturgical worship. Since that time, the struggle has been to regain an earlier approach to participation in the liturgy. The Liturgical Movement—whose legitimate concerns were foreshadowed by the radical actions of the Protestant Reformers—has come a long way toward re-integrating the laity and clergy into the one liturgical life of the Church.

The challenge has been to rebuild a sense of community. But the community cannot be left to itself; it must be given direction. The danger of the Liturgical Movement is that the pendulum could swing too far from a biblical perspective. If concern about gathering the people is devoid of it’s purpose of looking toward the advent of God’s kingdom, it looses its vertical shape. To complete renewal, the liturgy should form the people of God not just into a community, but into an eschatological community—a procession that moves in joyful anticipation toward the coming of the Lord.

If we are to return to a liturgy with a dominant eschatological shape, the biggest obstacle to overcome is our ingrained secularized perspective. Often the greatest challenge of believers in our age is to “lift up your hearts.” Change may come, but it cannot come until we turn our gaze back to the East and say with the psalmist:

I lift up my eyes to the hills—

from where will my help come?

My help comes from the Lord,

who made heaven and earth.

Monday, June 04, 2007

Sermon for Trinity Sunday

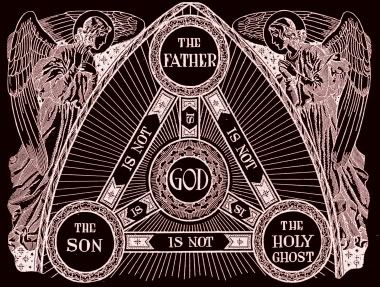

The classic Trinity diagram illustrating the relationships of the Persons of the Godhead.

You may listen to the sermon below by streaming audio or by download.

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

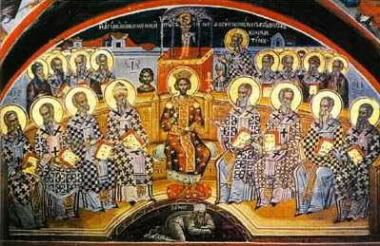

The year was AD 325 and Christian bishops from all over the known world were gathered to take council for the Church in the resort town of Nicæa. They were called together by Constantine, the first Christian Emperor. Constantine’s political aim was to unite the empire and a key part of that strategy was to have a united Church—which was not a problem, until . . . a priest in Alexandria, Egypt named Arius started making a pronouncement from the pulpit that “there once was a time when Christ was not.”

Arius taught that there was not always a co-eternal Son of God. His doctrine was that Jesus is instead the most exalted of all God’s creatures, whom God anointed with the Spirit at baptism and adopted as a son. He said Jesus is inferior to God, that he is not “God the Son.” Arius asserted that Jesus is of a different substance, that is, that Jesus is not fully divine like the Father is.

The bishops had come to Nicæa to sort out the matter. At one point, the conversation got so heated that the saintly bishop of Myra in Turkey, named Nicholas (Santa Claus) who was known for his kindness and generosity, walked over to Arius and punched him out. The story goes that Nicholas was immediately deposed for such unruly conduct, but the council restored him the next day when several of the bishops had a dream about Nicholas being returned to his episcopal throne.

What would bring such indignation out of a gentle man like Nicholas? What made Ole’ St Nick pop his top? Why was he so upset? Did it really matter that much what Arius was saying? Indeed, it does matter, for sometimes even words can destroy souls. The Apostle Paul wrote to St. Timothy, “Watch your life and doctrine closely. Keep doing this, for by doing so, you save both yourself and those who listen to you” (1 Tim 4:16-17).

Each year, after Eastertide and the feast of Pentecost, we celebrate the principal feast we call Trinity Sunday. At the end of the incarnation and redemption cycles of the kalendar, we pause to give thanks and embrace our heritage of faith, our faith in and worship of the one true God. He is the Holy Trinity—God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.

In the older prayer books, there was a creed called the Quincunque vult, proscribed to be read on Trinity Sunday and at one of the minor prayer offices. This creed was named after St. Athanasius, one of the great defenders of the orthodox trinitarian faith, even through great cost and personal hardship. This “Athanasian Creed” is printed at the back of the Book of Common Prayer. It is a creed that mainly describes the doctrine of the Holy Trinity—and in careful, exacting detail.

Like the indignant bishop Nicholas at the Nicene council, it is very serious-minded. In the first line, we read: “Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the Catholic Faith. Which Faith everyone do keep whole and undefiled, without doubt, he shall perish everlastingly. And the Catholic Faith is this: that we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity, neither confounding the Persons, nor dividing the Substance.”

Why does it matter so much? Why is it so important to keep the Catholic Faith whole, pure, and undefiled? Is it really so serious? Let us first realize that we know and identify God not just by name, but also by attributes. The same is true about other people; we know them both by name and by attributes. God has revealed to us certain things about himself, that reveal who he is. From the record of the Scriptures, we know that God is a person, that he is almighty and just, that he is also merciful, and that in the truest sense, God is love.

We read in the Bible that God has revealed himself as Father and that the Word and Spirit were involved in the act of creation. In the Scriptures we also learn that God has revealed his name—YHWH. God the Father names his only Son “Jesus,” which means “YHWH is salvation.”

In the New Testament, we learn that God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son to us. The Word was incarnate and dwelt among us. Jesus is the perfect icon of the Father, full of grace and truth. Jesus fulfilled the law and bore our sins on the cross.

He rose victorious from the dead and Jesus offers us the same blessing of new life by sacramentally joining us to himself as his mystical Body through the new birth of Baptism and the Eucharistic feast. When Jesus rose into heaven, taking our humanity into heaven, he did not leave us comfortless, but sent the Holy Spirit into our hearts crying, “Abba, Father.”

We know who God is and what he has done by his own self-revelation. That’s why we can be confident that we are not worshiping a false God, an idol, or a god that is simply the projection of our own selves. It is only through the one, true, and living God that we find salvation.

Stressing this point, St. Paul wrote to the Galatians, “I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting him who called you into the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel. . . ." And Paul goes on to say, “Even if we, or an angel from heaven, should preach to you a gospel which is different from the one we have been preaching, let him be eternally condemned (anathema). As we have said before, so now I say again: If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to the one you received, let him be eternally condemned” (Galatians 1:6-9). St. Paul goes so far as to give them back-to-back warnings—some doctrines can be soul-destroying. Arius was not merely tearing at the unity of the Church with his preaching, he was also destroying souls.

In the statement of faith issues at the end of the First Ecumenical Council, the Nicene Fathers rejected Arius’ doctrine that Jesus was an exalted creature, merely our ethical example, an earthly messiah, inferior to the Father. Drawing from the holy Scriptures and relying on the promise of Jesus that the Spirit would lead the apostles as a body and guide them into all truth, the bishops gathered at the Council of Nicæa affirmed: “We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, only-begotten of the Substance of the Father. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, being of one Substance with the Father.”

At the end of their doctrinal affirmation, the Fathers went on to say about Arius: And those who say, “There was a time when he was not,” and, “Before he was begotten he was not,” and that, “He came into being from what is not,” or those who allege, that the son of God is “of another substance or essence”, or that he is “created” or “changeable,” these the Catholic and Apostolic Church declares anathema.

They didn’t have the political concern that Constantine did. But when the bishops in council saw the damage to souls from not being clear about those preaching a different gospel and proclaiming a different God (a god other than the holy Trinity), they were all just as indignant as Bishop Nicholas of Myra.

What is the lesson to us today from the councils of the Church that defined and defended the Christian concept of God as the Holy Trinity? What can we learn from it all? I think there are at least two lessons we should pull from the Church’s experience of dealing with false doctrine, conflict, schism, and resolution.

First, as the Apostle Paul said, “Watch your life and doctrine closely. Keep doing this, for by doing so, you save both yourself and those who listen to you” (1 Tm 4:16-17). Let us become so familiar with who God is and what he is like, that we instantly recognize when someone tries to pass us a counterfeit.

When we hear the persons of the Trinity described as “aspects of God,” when we hear that “the Father came down to be one of us,” or that Jesus was merely a human being, or only appeared human, or that Jesus became God, or stopped being God on the cross, or that diversity is what makes God a trinity, or that the Holy Spirit is an “it”—a thing, or that you and I are little gods or “gods-in-embryo,” then we should not pay attention to anything else they have to say. For these are the beginnings of errors, not the end. And sometimes, words can destroy souls.

Second, let us have faith in God that he will preserve the holy Faith of his Church. Arianism was the most destructive heresy to ever rise in Church history. The bishops thought it was all over atNicæa, only to see the heresy later morph into other forms. Just when it seemed to be resolved, an Arian would become emperor and therefore many Arians would be appointed as bishops. It is estimated that at one point, over 80% of the Church was Arian and as a result, orthodox bishops, clergy, and lay Christians were persecuted as enemies of both Church and state.

But Christ built his Church on a rock, the gates of hell never to prevail against it. They would not prevail then, and they will not prevail now. Why? Because Christ promised, and that is sufficient. Christ promised that the Spirit would lead us into all truth. Deception, confusion, and misunderstanding are overcome by the Truth of God as revealed in his holy Word.

Do not be discouraged by being on the small side, as long as you are on God’s side. Even if you are the only one standing up for truth, you are on the winning side. They had a saying about those early struggles in the church over Arianism. It was Athanasius contra mundum—“Athanasius against the world.” Too bad for the world. Athanasius won. His side was triumphant. It was not because Athanasius was smarter, more skilled, or more dedicated. It was because Athanasius did not stand alone; he stood on God’s side.

He knew God personally, and constantly strove to make him known more fully—God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit . . . one God, one being, co-equal, co-eternal.

Let us pray. Most glorious Trinity: Give us grace to continue steadfast in the confession of this faith, and constant in our worship of you, O Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; who lives and reigns, one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

Friday, June 01, 2007

Teed off for Christ

I had a great time at my first entry in the Bishop Iker Golf Challenge. I played 18 holes with these fine gentlemen from Ss Peter and Paul in Arlington. We scored a 75 (3+par). It was a beautiful day and a nice course. Best of all, the event raises money for our diocesan ministry at Camp Crucis and funds scholarships for campers.

Tuesday, May 29, 2007

Anglican and Catholic

From time to time, I sneak a peek at the Rector's copy of The Living Church, the Episcopal Church's last weekly independent news magazine. I was delighted to find the editorial below on page 24 of this week's issue about going back to their roots. I say good for them, and good for us.

When the Board of Directors of the Living Church Foundation met recently in Albuquerque, N.M., it spent some time discussing the role of this magazine in a rapidly changing Episcopal Church and Anglican Communion. Members of the board felt this would be a good time to clarify the role and purpose of THE LIVING CHURCH. In so doing, the board felt it should return to its roots and re-emphasize its historic mission.

The Articles of Incorporation of the foundation, publisher of this magazine, state that its purpose is "the publication and distribution of literature in the interest of the Christian religion, and specifically of the Protestant Episcopal Church according to what is commonly known as the Catholic conception thereof..." That document, written nearly 80 years ago, also acknowledges that such publication and distribution includes "conducting and maintenance of a printing and publishing business..."

Readers may notice that beginning with this issue we have attempted to explain our purpose in two statements. One is found on the cover immediately underneath the masthead, or name of the publication. Gone is the familiar "An independent weekly serving Episcopalians." In its place is this description: "An independent weekly supporting catholic Anglicanism." This does not represent a change in our focus, but rather it broadens what has been our position all along.

THE LIVING CHURCH has always served Episcopalians and will continue to attempt to do so, but it has always served other Anglicans as well. For many years this magazine has contained news and articles about other Anglican churches, because we believe the Anglican Communion is important. We have long emphasized the importance of Episcopalians being Anglicans, and now is a good time for us to re-emphasize it.

The second statement that has been rewritten is found at the top of Page 3. It clarifies the historic mission of the Living Church Foundation. We are committed to the Anglican and catholic concept of the church as an incarnational and sacramental body. We value our Anglican heritage and take seriously our role as catholic Christians. We attempt to nourish Anglican faith, piety and practice within The Episcopal Church. Again, this represents no change in our policy. Rather it is simply time that we said so.

By the way, that is not a photo of the Board of Directors of the Living Church (if only). It is the photo taken outside of St Paul's Cathedral, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, after the consecration of Bishop R. H. Weller in 1900. The picture, dubbed the "Fond du Lac Circus," was published in The Living Church and created controversy in southern low church parishes who had never seen such pomp and circumstance. I have the picture hanging in my office.

Sermon for the Feast of Pentecost

This past Sunday, I visited one of the new mission congregations of our diocese, St Barnabas the Apostle in Keller, TX. Thanks to the good people of St Barnabas, the audio of my homily is available online. You may listen to it by streaming audio or by download. I will also be there next week, on Trinity Sunday, and will post the links to that homily when it becomes available.

Visions of the Messiah

Joel 2:28

"And afterward, I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, your young men will see visions."

For the past few years, we have been seeing news accounts of Muslim conversions to Christ through dreams and visions. Evangelism among Muslims, especially in Islamic territory has been difficult since the attempt of St Francis of Assisi. The Sultan remain unconverted, but his last words to the departing Francis were, "Pray for me that God may deign to reveal to me that law and faith which is most pleasing to him." Along the lines of St Peter's Pentecost sermon citing the prophet Joel (above), the Holy Spirit seems to be addressing this problem.

"There is an end-time phenomenon that is happening through dreams and visions," said Christine Darg, author of The Jesus Visions: Signs and Wonders in the Muslim World. “He is going into the Muslim world and revealing, particularly, the last 24 hours of His life - how He died on the cross, which Islam does not teach - how He was raised from the dead, which Islam also does not teach – and how He is the Son of God, risen in power."

More recent is the somewhat different story of Rabbi Yitzchak Kaduri, who allegedly claimed to have visions of the Messiah before his death.

Before Kaduri died, he reportedly wrote the name of the Messiah on a small note, requesting it remained sealed for one year after his death. The note revealed the name of the Messiah as "Yehoshua" or "Yeshua" – or the Hebrew name Jesus. . . .

The note, written in Hebrew and signed in the rabbi's name, said: "Concerning the letter abbreviation of the Messiah's name, He will lift the people and prove that his word and law are valid. This I have signed in the month of mercy." The Hebrew sentence consists of six words. The first letter of each of those words spells out the Hebrew name Yehoshua or Yeshua.

As reported by Israel Today:

A few months before Kaduri died at the age of 108, he surprised his followers when he told them that he met the Messiah. Kaduri gave a message in his synagogue on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, teaching how to recognize the Messiah. He also mentioned that the Messiah would appear to Israel after Ariel Sharon’s death. (The former prime minister is still in a coma after suffering a massive stroke more than a year ago.)

Other rabbis predict the same, including Rabbi Haim Cohen, kabbalist Nir Ben Artzi and the wife of Rabbi Haim Kneiveskzy. Kaduri’s grandson, Rabbi Yosef Kaduri, said his grandfather spoke many times during his last days about the coming of the Messiah and redemption through the Messiah. His spiritual portrayals of the Messiah—reminiscent of New Testament accounts—were published on the websites Kaduri.net and Nfc:

“It is hard for many good people in society to understand the person of the Messiah. The leadership and order of a Messiah of flesh and blood is hard to accept for many in the nation. As leader, the Messiah will not hold any office, but will be among the people and use the media to communicate. His reign will be pure and without personal or political desire. During his dominion, only righteousness and truth will reign.

Monday, May 28, 2007

Memorial Day photos

Almighty God, our heavenly Father, in whose hands are the living and the dead: We give thee thanks for all thy servants who have laid down their lives in the service of our country. Grant to them thy mercy and the light of thy presence; and give us such a lively sense of thy righteous will, that the work which thou hast begun in them may be perfected; through Jesus Christ thy Son our Lord. Amen. (Book of Common Prayer, p 488)

Sunday, May 27, 2007

The simple style of ancient hymns

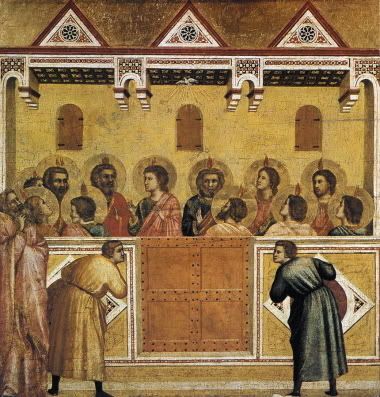

I love how ancient hymns very simply and poetically tell the story straight from the Scriptures. The example below (which may offend some) is the first hymn at Matins on Pentecost. The source of beautiful translation is the Anglican Breviary. For comparison, the story is recorded in Acts 2:1-21.

Hymn at Matins: Jam Christus astra ascenderat.

Now Christ, gone thither, whence he came,

And throned midst the stars aflame,

Desired God's Promise to bestow,

The Father's Gift to man below.

The solemn time was drawing nigh,

Replete with heavenly mystery,

On seven days' sevenfold circles borne,

That first and blessed Whitsun-morn.

When the third hour shone all around,

There came a rushing mighty sound

And told the Apostles, while in prayer,

That, as 'twas promised, God was there.

Then from the Father's light there came

That beautiful and kindly Flame,

To kindle every Christian heart,

And fervour of the Word impart.

With joy the Apostle's breasts are fired,

Thus by the Holy Ghost inspired;

And straight, in divers tongues and speech,

That wondrous works of God they preach.

All nations to their voice give ear;

Barbarians, Latins, Grecians hear,

And lo, the wondrous word to all

Doth in familiar accents fall.

But Jewry, faithless even yet,

With mad, infuriate rage beset,

To mock Christ's followers, combine,

As drunken all with new-made wine.

Thereat, with signs and works of might,

Stands Peter forth to teach aright

How Joel's words, fulfilled this day,

Refute what these maligners say.

To God the Father, God the Son,

And God the Spirit, praise be done;

And Christ the Lord upon us pour

The Spirit's gift for evermore. Amen.

Monday, May 21, 2007

Is it censorship?

12"Behold, I am coming quickly, and my reward is with me, to render to every man according to what he has done. 13 I am the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end." 14 Blessed are those who wash their robes, so that they may have the right to the tree of life, and may enter by the gates into the city. 15 Outside are the dogs and the sorcerers and the immoral persons and the murderers and the idolaters, and everyone who loves and practices lying. 16 "I, Jesus, have sent my angel to testify to you these things for the churches I am the root and the descendant of David, the bright morning star." 17 The Spirit and the bride say, "Come." And let the one who hears say, "Come." And let the one who is thirsty come; let the one who wishes take the water of life without cost. 18 I testify to everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this book: if anyone adds to them, God will add to him the plagues which are written in this book; 19 and if anyone takes away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God will take away his part from the tree of life and from the holy city, which are written in this book. 20 He who testifies to these things says, "Yes, I am coming quickly " Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.

The most interesting part about the editing is that one of the verses which is omitted is a condemnation of those who remove passages from the book. The context would seem to indicate that John has in mind removing passages from being read out loud in church.

It is not simply a '79 Prayer Book issue. As you can see from Textweek, it is simply the same selection taken from the original three year lectionary developed by the Roman Catholics for the Missal of Paul VI, which was adopted without substantial change by other western liturgical churches. The difference is that the Prayer Book expressly allows omitted verses to be read or readings to be otherwise lengthened (see BCP, p 888).

The question to ask is why the passages were omitted. Admittedly, the list of the damned and the condemnations don't fit nicely into a rosy Easter selection. But is this ample reason to censor them? I would say no. But I would also suggest that if such passages are not read in church, they simply will not be heard by most people in the pew who simply do not read the bible regularly on their own. With one passage, it may not make that big of a difference. But with all the edited passages in the lectionary, it could have a cumulative effect of distorting the perception of the faith among many in the pew. Even those aware of such passages need to be reminded periodically of their existence.

Titusonenine is having a discussion about whether the omissions represent a move toward a universalist theology. It is worth taking a look.

Sunday, May 20, 2007

Homeward bound

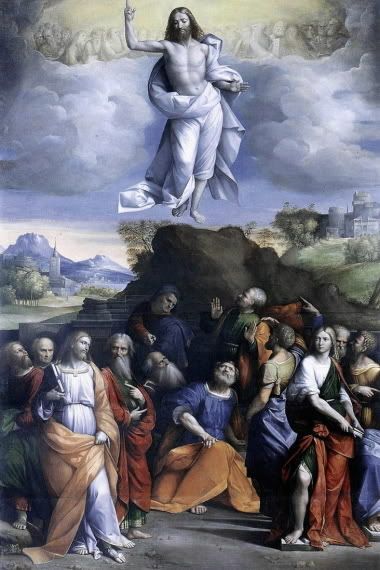

They did so. Still today, we keep a special nine-day vigil of prayer called a novena between the Ascension and the coming of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost. But I’m sure their attention was still turned toward heaven, pondering the mysteries that lay unseen on the other side of the cloud. And so in this time for us between the Ascension and Pentecost, it’s good that we also turn our attention toward heaven and seek understanding. This is a good time to address the subject, and there’s no better place to learn about heaven than here in church. While we don’t have the time to be exhaustive on this occasion, I did want to address a few basic concepts about heaven.

First, What is heaven? What is this heaven to which Jesus has ascended? We sometimes use that word in passing without considering its meaning. What is heaven? Is there one answer to that question? Would I recognize heaven if I saw it? The Bible has much to say about heaven, but the manifold metaphors and details are sometimes hard to separate and analyze and understand. Pearly gates? Streets of gold? Walls of jewels? Is heaven a magnificent palace?

Behind the many references to heaven, I think we can find one central concept: heaven is the abode or dwelling-place of God. Therefore, in going to heaven, Jesus goes home to the Father. Heaven is God’s dwelling-place, but he does not want to dwell in solitude. As creatures made in God’s image, we were fashioned to share more and more fully in the life of heaven—to be at home with God. This is the sense in which the Prayer Book defines heaven: “By heaven, we mean eternal life in our enjoyment of God” (BCP, 862).

This is what theologians have called the Beatific Vision: the fullest experience of heaven is the intuitive and unobstructed knowledge of God as he is—that is, to behold God face-to-face. And this intimate communion with God becomes the source of everlasting happiness for the human soul. This is what we pray for at funerals. The catechism says we pray for the dead, “because we still hold them in our love, and because we trust that in God’s presence those who have chosen to serve him will grow in his love, until they see him as he is” (BCP, 862). This is the Beatific Vision.

Let us not forget, however, that the joys of heaven are not only found in fellowship with God, but also in the joys of fellowship with those we love. That means being reunited with family and friends. It means the joy of getting to know family members we have heard about but have never met because they died before we were born. Sharing a home with God means sharing that home with others.

Second, we are led to ask, Where is heaven? Despite the fact that Jesus ascended into a cloud in the sky, it does not follow that heaven is necessarily “up there” somewhere on the other side of the clouds. Indeed, if heaven is God’s dwelling-place, it seems that earth might be considered a part of heaven in the beginning, when God walked and talked with Adam and Eve in the garden paradise of Eden. It was certainly heaven for them. Yet, in a sinful world, God seems distant—above and beyond the toils and tragedies that we know in the here-and-now. Wherever heaven is, we feel it is surely apart from earth.

Now Jesus prepares a new heaven for us. The Book of Revelation speaks of a new heaven and a new earth, where God dwells perpetually with his people in a common home. “The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in the city, and his servants will serve him. They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads” (Rev 22:3-4).

Theologian Karl Rahner put a new spin on what heaven means for us. He observed that instead of looking at Jesus as going to a pre-existing place called heaven, we could instead say that Jesus returned to the Father to establish heaven as the fulfillment of the promised union of humanity with God, begun with the union of the human and divine within Christ at the incarnation.

Likewise, when Christ returns to earth in glory, it’s not so much that he leaves heaven as it is that he brings heaven with him and remakes a heaven out of earth. “The seventh angel sounded his trumpet, and there were loud voices in heaven, which said: ‘The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ, and he will reign for ever and ever’” (Rev 11:15). That sounds like something worth being a part of.

So thirdly let us consider, Who goes to heaven? Or to put it another way, How do I get there? It is said that there will be three surprises in heaven: The first surprise finding people in heaven that you never expected to be there. The second surprise is looking around for those you expected to see in heaven, but not being able to find them there. And the third surprise is that you are there. What a joyful surprise that is! And it should surprise us, for Jesus is really the only human being who belongs in heaven. But remember that God does not want to dwell alone.

When Jesus told his disciples he was going to prepare a place for us and we know the way to follow, “Thomas said to him, ‘Lord, we don’t know where you are going, so how can we know the way?’ Jesus answered, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me’.” (Jn 14:5-6)

Since only Jesus belongs in heaven, he is our only way into heaven. We don’t belong because we have been estranged by sin. But Jesus atoned for our sins and made forgiveness possible. Through his incarnation, death, resurrection, and ascension, he has become the means for restored fellowship with God. So the way to heaven is being “in Christ,” as St Paul so often expressed it. It means that we are joined to him, united to him, share his resurrected life. If we make our home in Christ, we will find ourselves in heaven. That's why Jesus prayed in today's Gospel reading that we may find our unity by dwelling in the Son, who is one with the Father.

Ontologically, this union begins with baptism. The sacrament of Holy Baptism is our death to our old selves and our rebirth into the resurrected eternal life of Christ. "We were therefore buried with him through baptism into death," as St Paul wrote to the Church in Rome, "in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, we too may live a new life" (Rom 6:4). Likewise, Holy Communion, “the Bread of heaven,” sustains that intimate fellowship with God and sharing of resurrected that comes through first being joined to Christ when we are born again at our baptism.

As you come to the altar today, to the sanctuary where heaven overlaps with earth, know that you come to find a foretaste of our promised inheritance, for all the glories of the risen Christ have ascended into the sacraments.

We therefore beg, dear Lord of thee

To pardon our iniquity;

Yea, of thine own supernal grace

Uplift our hearts to seek thy face:

That when in clouds, O Judge of doom

Thy glory shall this earth illume,

Thou mayst remit our debt of pain,

And grant our long-lost crowns again.

All praise from every heart and tongue

To thee, ascended Lord, be sung;

Whom with the Father we adore,

And Holy Ghost, for evermore. Amen.

Thursday, May 17, 2007

Painted ceilings are worth looking up to

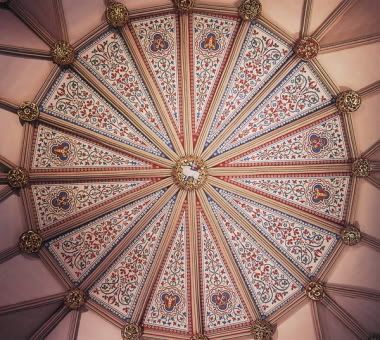

On this feast of the Ascension of our Lord, my attention is drawn to the painted ceilings of churches. The ceiling of the chapter house of the cathedral at York (above) shows the central role of Christ, the Lamb of God, in the Catholic Faith.

The blue ceiling with gold stars at the Church of St Mary the Virgin in New York City (above) reminds one of the celestial realms of glory. It is a common ornamentation for the sanctuary. The blue ceiling with gold "MR" in the Cathedral of St John the Evangelist in Spokane (below) reminds us of Maria Regina--Mary, the Queen of heaven.

The soft blue and white on the ceiling of Worcester Cathedral (above) convey a sense of the gentleness of the Lamb of God. The detailed painted saints and ornament on the ceiling of St Paul's Cathedral in London (below) remind one of the glories that await in heaven.

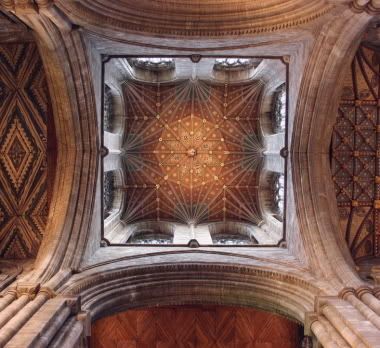

The color in the tower at Canterbury Cathedral (above) highlights the architectural structure, as does the contemporary look in the cathedral of Madrid (below).

Monday, May 14, 2007

To elevate or not to elevate

I realize that this post may only interest priests, sacristy rats, and other liturgy geeks, but so be it. One of the things that has been awkward in the most recent Prayer Book (and even in the previous editions) is exactly how to handle the alms, or monetary offerings. If you are looking for ceremonial directions in those old books that deal with Catholic liturgical minutia, forget it.

The other day I heard someone say (tongue-in-cheek) that downtown at St Andrew's (our traditional low-church parish) they won't elevate the host, but they sure will elevate the cash. Of course, we see it handled slightly differently everywhere. In some places, very simply. In others, it is like a solemn blessing of the cash (perhaps to exorcise it's attraction as the source of all evil). So that got me thinking. Exactly how do you handle the cash?

As far as the liturgy is concerned, there is much detail about the offerings and the offertory. But in that case, the offerings ("oblations" as distinct from "alms" and "offerings" in the 1928 BCP) are the bread and wine. The directions from the 1928 Prayer Book on this matter are as follows:

¶ The Deacons, Church-wardens, or other fit persons appointed for that purpose, shall receive the Alms for the Poor, and other Offerings of the People, in a decent Basin to be provided by the Parish; and reverently bring it to the Priest, who shall humbly present and place it upon the Holy Table.

¶ And the Priest shall then offer, and shall place upon the Holy Table, the Bread and the Wine.

¶ And when the Alms and Oblations are being received and presented, there may be sung a Hymn, or an Offertory Anthem in the words of Holy Scripture or of the Book of Common Prayer, under the direction of the Priest.

Some things I notice in these rubrics: The money is received in a basin by someone assisting in the liturgy--be that a deacon, warden, subdeacon, or acolyte. The basin is given to the priest. No ceremony seems to be implied; it is not held up for him to bless. The celebrant in turn "shall humbly present and place it upon the Holy Table."

In these directions, the basin of alms is to be left on the altar. That the priest "humbly presents" it, implies some ceremony. That could mean that he should hold it up in the gesture of offering, or make the sign of the cross over it, or both. The sign of the cross will likely be made over alms in the "Prayer for the whole state of Christ's Church" at the words, "We humbly beseech thee most mercifully to accept our [alms and] oblations, and to receive these our prayers, which we offer unto thy Divine Majesty". Then comes the offering of bread and wine, which may have been sitting off the corporal, waiting for the alms to be collected and placed on the altar.

Here a note should be made about the two different gestures known by the word "elevation." The more familiar gesture is what is called the "major elevation," which first appeared in the Western liturgy in the thirteenth century. In this case, after the applicable words of consecration, the priest raises the element up higher than his head to show it to the people for their adoration.

The older "minor elevation" comes later at the doxology to the eucharistic prayer. In this case, it is a gesture of offering ("Thine own, from thine own, we offer unto thee"). The priest raises the Host and Chalice together up to about chest (or at most, eye level). This was also the type of gesture used at the offering of bread and wine before the eucharistic prayer began. It seems to me that this is the gesture that should be used by the priest, if any, for the presenting and placing of alms on the altar.

What is sometimes seen is that the alms basin is raised up over the head (as pictured above). Although there is a subtle difference between the two gestures of elevation, the main problem in this case is that the elevation over the head is a gesture of adoration. There only other place it appears is in the adoration of the consecrated Host and Precious Blood. Needless to say, it is not appropriate for the cash. Especially when accompanied by the singing of "Praise God, from whom all blessings flow," the gesture gives the impression that we are praising Mammon.

In contrast to the 1928 edition, the 1979 Prayer Book does not give much guidance for how to go about handling the offertory. The main direction seems to be that the people must stand, at least when gifts are first put on the altar.

Representatives of the congregation bring the people's offerings of bread and wine, and money or other gifts, to the deacon or celebrant. The people stand while the offerings are presented and placed on the Altar.

It seems to me that in absence of more explicit direction (which should be given in the next revision) or contrary instruction, the older pattern should adhered to with the dignity and decorum fitting the offering of alms.

Thursday, May 10, 2007

What hue shall we do?

At the recommendation of the flower guild and the worship committee, the wall of the apse here at St. Alban's will be painted blue, probably this week. The motive is to make the candles and flowers stand out better against the background. Blue and red accented with gold are the most common colors for the sanctuary. Of course, we have a lot of red here with the brick. And blue also makes sense for our apse since the archway at the crucifix represents the open gateway to heaven and our columbarium is placed in the walkway of the apse.

Now the question is which hue is best. I'm inclined toward the idea that darker is better, preferably with some sacred symbols stenciled in gold, but it's also not my decision. Some sample patches have been painted for comparison. The final choice will be a light to medium grayish blue, somewhat similar to the altered photograph below.

I have added an example of what I refer to above and in the comments about a darker blue background accented with gold symbols like the fleur-de-lis. The picture is of the main altar designed by A.W. Pugin at the Church of Ss Peter and Paul in Newport, Shropshire (UK).

Monday, May 07, 2007

Glimpses of glory, a homily for Easter V

One of the most spectacular meteorological phenomena in the world is a rare cloud formation called the cloud of Morning Glory. Usually, it is only observed in Northern Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria. A Morning Glory cloud can best be described as a roll cloud that can be more than 600 miles long, over a mile tall, and can move at speeds up to 25 miles per hour.

The morning glory is often accompanied by sudden wind squalls, intense low-level wind shear, and a sharp pressure jump at the surface. In the front of the cloud, there is strong vertical current that sends air up in the cloud and creates the rolling appearance, while the air in the back side becomes turbulent and sinks. The cloud can also be described as a Solitary wave, a wave that has a single crest and moves without changing speed or shape. Despite being studied extensively by Australian meteorologists, the Morning Glory cloud is still not clearly understood.

At once both entrancing and frightening, it essentially looks like a giant white tidal wave in the sky. It was named “morning” because that is the usual time of day when the formation appears, due to the moisture in the atmosphere. The name “glory” comes from the awesome display of the energy in motion by the clash between hot and cold. No one would deny this formation the word "glorious." But is glory best illustrated by this gigantic cloud, or by the gentle flower called the Morning Glory?

Glory is something which is seen or experienced, more than understood. Indeed, it is difficult to come up with one definition to understand the word "glory." Glory is perhaps instead a quality that best helps us understand something else. For this reason, God uses ordinary things as signs of his glory.

The things are “ordinary” in the sense that they are natural things that we experience everyday—like sunshine, clouds, fire, hail, beauty, acts of kindness, music, or most anything else. God uses ordinary things for extraordinary purposes. God uses them to get our attention, to convey a mystery, to reveal his majesty. The Greek word for glory, doxa, indicates a worthwhile quality. The Hebrew word for glory, kabhod, comes from the root for heaviness. God uses ordinary things as signs of the weight of his glory.

Isaiah pointed this out. He liked to use the word "signal" (or “ensign” in the King James Version). Simple things are used as ensigns to call people to come experience God’s glory. In chapter 11, the Prophet writes, “And in that day there shall be a root of Jesse, which shall stand for an ensign of the people; to it shall the Gentiles seek ... he shall set up an ensign for the nations, and shall assemble the outcasts of Israel, and gather together the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth.”

The simple birth of a child heralds the glorious dawn of eternal salvation. Jesus is the ultimate sign of God’s glory—his life and death and resurrection reveal that glory. When the Christ child was presented in the Temple, the aged Simeon recognized it, saying that he was now ready die in peace. "For my eyes have seen thy salvation, which thou hast prepared in the sight of all people, a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to thy people Israel.” A baby was the sign of the glorious dawn of salvation.

What makes something a sign of glory is not the dramatic nature of the sign, but the importance of that which it is used to reveal? For this reason, true glory is often hidden from view. Many people look upon the sign and see something ordinary. Others discern the glory and are brought to their knees in humble recognition of divine majesty.

In today’s gospel reading, Jesus said, “Now has the Son of Man been glorified, and God has been glorified in him.” Is this the moment we’ve all been waiting for? Is this the unveiling of the majesty of the Father and the Son? An outside might have missed it entirely, but then I don’t know if the insiders fared much better. And yet, according to what Jesus said, this is the moment.

The curtain is rising, the search lights are beaming, the trumpets are blasting, heaven and earth are calling our attention. The betrayer has just sealed Jesus’ destiny. Judas has chosen to go through with his plan of betrayal, which means that the hour of glory has come—the crucifixion of our Lord Jesus Christ.

The resurrection was a more direct display of God’s power. The ascension called our attention to the heavenly realms of glory. Yet, the it is the crucifixion which occupies “the hour of glory” in John’s Gospel. That is to say, all the glories of the risen and ascended Christ are fully unveiled in his passion and death. There is no glorious moment in the story of the good news than when the Lord of heaven and earth pours himself out in love so that sins may be forgiven and the gates of heaven be opened. There is no more glorious thing than sacrificial love.

To put it another way, true glory is not found in the reward, but in the sacrifice. Think of a great monument; the glory is not in the monument, but in that which it commemorates. The most glorious thing is love, and the nature of love is the gift of self. Now that they are going to be separated, Jesus called upon his disciples to follow that example. He called them anew to the love which fulfills all the commandments of God. "I give you a new commandment: Love one another the way that I have loved you.” That is, I want you to give yourselves away for others, as I will do for you. That's how people will know that you are my disciples.

Christians are supposed to love God and to love one another. That means giving ourselves away . . . to God, to each other, and to those who will come after us. That’s what it means to love; that’s what it means to truly live. Quaker philosopher Elton Trueblood once wrote, “A man has made at least a start on discovering the meaning of human life when he plants shade trees under which he knows full well that he will never sit.”

The Father is gloried by the perfect obedience of the Son, even unto death. The Son is glorified by the Father in manifesting divine love to the world. Some of the most glorious things often look the most ordinary—the birth of a baby, the execution of a criminal, or the unfolding of a morning flower. All of God’s glories shine through the light of the cross.

The most glorious among us are the most Christ-like among us. That Christ-likeness involves looking to the future, seeing what the real priorities are, and putting others before ourselves as an expression of love. I submit to you today that this is the most glorious way to live—living as a sign for others, living lives of sacrifice, the majesty of giving ourselves away.

Sunday, May 06, 2007

The mysteries of Marmite

Marmite is that oh-so-English savory spread for toast and so much more. It is a syrup made from yeast extract produced in brewing beer. What I did not know until recently is that supposedly, if you put a dollop of Marmite on a plate and whack it repeatedly with a spoon, it will turn lighter in color. Some have reported that it will turn nearly white, but I have not found any documentation of this. The picture below shows Marmite that has been whacked. The dark splotch on the left is a fresh dollop of Marmite for color comparison.

Update: From our UTA Canterbury director Brian Pickard, here is the sermon from his parish last Sunday. The visiting preacher, Bishop Benjamin Kwashi of Jos, mentions growing up with Marmite about half-way through. The title of his sermon? It's "Are you afraid of hell?"

Wednesday, May 02, 2007

Why God made hugs

An older gentleman who regularly attends our Saturday morning Mass and is always ready to give out free hugs gave me a bookmark with this delightful poem by Jill Wolf.

Everyone was meant to share

God all-abiding love and care;

He saw that we would need to know

A way to let these feelings show.

So God made hugs--a special sign,

And symbol of His love divine,

A circle of our open arms

To hold in love and keep out harm.

One simple hug can do its part

To warm and cheer another's heart.

A hug's a bit of heaven above

That signifies His perfect love.