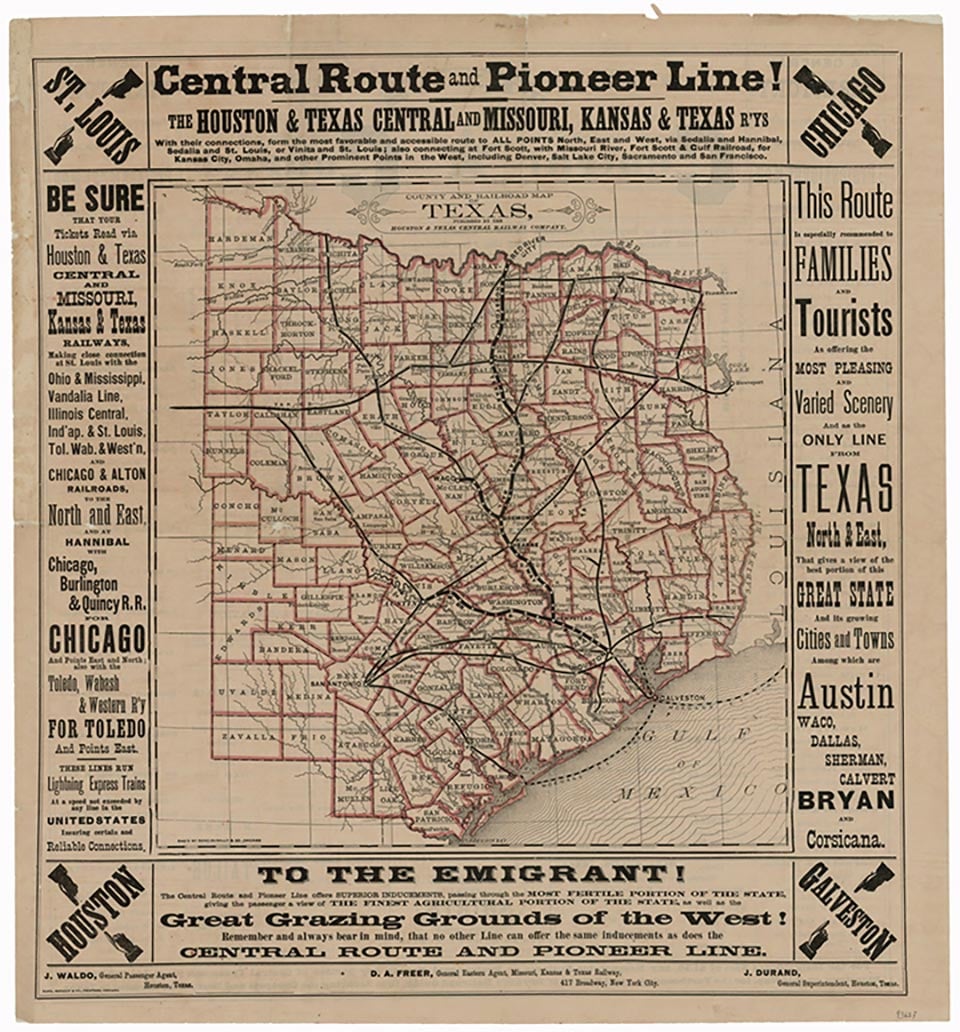

Although it is only a state agency, the Texas Railroad Commission has been historically one of the most important regulatory bodies in the nation. This is because for much of the twentieth century it has strongly influenced the supply and price of oil and natural gas throughout the United States. As its name implies, the commission was originally established to oversee railroads. Riding a wave of Populist-style resentment of the railroads, James S. Hogg won the governorship in 1890 largely on his promise to have them regulated. The state constitution had been simultaneously amended to allow such a body, and in 1891 the legislature established the commission, giving it jurisdiction over rates and operations of railroads, terminals, wharves, and express companies. Governor Hogg's first appointments were John H. Reagan (chairman), Judge William Pinckney McLean, and Lafayette L. Foster. In 1894 the legislature made the agency elective, the three commissioners henceforth serving six-year, overlapping terms in Austin.

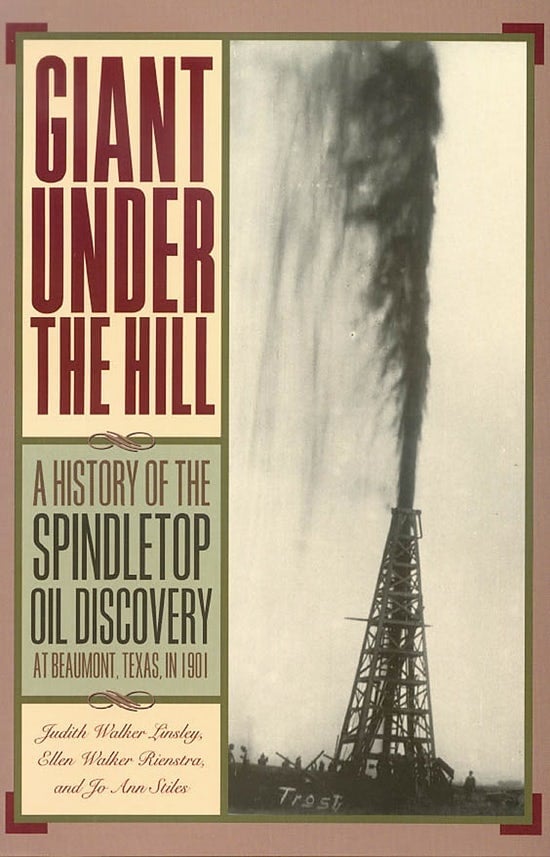

Despite the fact that the federal Interstate Commerce Commission preempted the regulation of interstate transportation, and despite inadequate funding and occasionally hostile court decisions, the Railroad Commission in its first years had some success in restraining intrastate freight rates. In the twentieth century the commission has continued to regulate intrastate railroads, and has had buses and trucks added to its transportation responsibilities. Its importance to the state and nation, however, has rested on its authority over the energy industry. In 1917 the legislature granted the commission the authority to see that petroleum pipelines remained "common carriers"-that is, that they did not refuse to transport anyone's oil or gas. Two years later, commissioners received responsibility for promulgating well-spacing rules. In the early 1920s the agency accepted jurisdiction over gas utilities. This gradually growing responsibility prepared the way for the enormous expansion of commission activity during the next decade. In the early 1930s unrestrained production from the huge East Texas oilfield caused the price of crude to plummet worldwide and created consternation in the industry. To stabilize oil prices and to help conserve the valuable resource, a coalition consisting of parts of the industry, scientists, and public officials attempted to have output regulated. This coalition was soon ably led by Ernest O. Thompson, who was appointed to a vacancy on the commission by Governor Ross Sterling in 1932.

After an involved, protracted, and occasionally violent political struggle, the Railroad Commission won the authority to prorate, that is, to set the rate at which every oil well in Texas might produce. By limiting production in East Texas and elsewhere, commissioners succeeded both in supporting oil prices and in conserving the state's resources. Under the Connally Hot Oil Act of 1935, the federal government undertook to enforce in interstate commerce the production directives of the Texas commission and its sister state agencies. When the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries was organized, the Railroad Commission was used as a model. Because of its ability to prorate Texas oil production and because of this state's crucial role in the petroleum industry, the Railroad Commission was until the early 1970s of vital importance to national and international energy supply. With the decline of Texas oil reserves, the great increase in world demand, and the rise of OPEC, however, the commission's influence over oil has dwindled. Today, its responsibilities in this area consist mainly of enforcing cleanliness in the fields and maintaining equity among producers.

If its influence over oil has declined, however, the commission's responsibility for natural gas has greatly expanded. There were abstruse and locally intense conflicts over gas in the 1930s. Because gas was of relatively lower value than oil, however, commission policies in this area were less developed and of less interest within the industry and to outsiders. This changed in the following decade. Because gas was so relatively valueless, oil operators in that era commonly burned ("flared") the casinghead gas that they inevitably produced with their oil. By the mid-1940s, about a billion and a half cubic feet of natural gas a day was being lost statewide. In 1947, under the prodding of a new member with a petroleum engineering background, William J. Murray, Jr., the commission issued orders that effectively forbade the flaring of casinghead gas. This action not only preserved an irreplaceable natural resource, but, by forcing producers to return gas to reservoirs, sustained their pressure, thus significantly increasing the recovery of oil. Gas acquired considerable importance again in the 1970s. When the Lo-Vaca gathering company became unable to meet its contracts to supply natural gas to four million South and Central Texas consumers in the winter of 1972–73, the Railroad Commission, by virtue of its authority over gas utilities, inherited a political quandary. To allow Austin, San Antonio, and Corpus Christi to run out of gas was unthinkable. Yet further supplies were available only at much higher prices, which would impose higher utility bills on consumers. Amid almost constant bad publicity, and in a context of increasing natural gas prices, commissioners struggled with this problem for seven years. In September 1979 they finally ratified a complex compromise that was minimally acceptable to the parties involved. More problems with gas occurred in the 1980s. The federal Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 imposed a complex regulatory framework on Texas producers, yet required the state to assume responsibility for implementation. Railroad commissioners are consequently faced with the unappealing prospect of enforcing a multitude of ambiguous rules on a resistant state industry, while fending off criticism from Washington. Thus, although the commission's involvement in oil policy has drastically declined, it remains an important actor on the national energy stage.

In the early 1990s the commissioners oversaw an agency consisting of four regulatory divisions: Oil and Gas, Transportation-Gas Utilities, Surface Mining and Reclamation, and Liquefied Petroleum Gas. The Oil and Gas Division maintained ten district offices for the purpose of the monitoring and inspection of oil and gas operations. The Legal Division of the commission provided legal support. The Oil Field Theft Investigation Unit, organization in 1987, provided statewide law-enforcement assistance regarding oil and gas and drilling-equipment theft and conducted audits of oil-related businesses. For 1992 and 1993 the Railroad Commission was authorized 947 employees. The budget was over $47 million for each of these years.